The Lover’s Eyes

As objects, lover’s eyes are mesmerizing—and bizarre. Part-portrait, part-jewel, they resist easy categorization. They’re also steeped in mystery: In most cases, both the subject whose eye was depicted and the artist who painted it are unknown.

In 1785, when Maria Anne Fitzherbert opened a love letter from her admirer, Prince George of Wales, she wasn’t expecting to find an eye, gazing intently back at her.

The British prince was lovesick—and desperate. He’d fallen hard for Fitzherbert, but their courtship had been disastrous: Royal laws forbade a Catholic widow like his beloved from becoming a monarch. To make matters worse, the upstanding Fitzherbert had fled the country after the prince’s first proposal, in an attempt to avoid controversy.

But the prince was determined, and on November 3rd, he penned a passionate letter begging again for her hand in marriage. This was no ordinary proposal, though—it also contained a rare, spellbinding gift. “I send you a parcel,” George wrote in the letter’s postscript, “and I send you at the same time an Eye.”

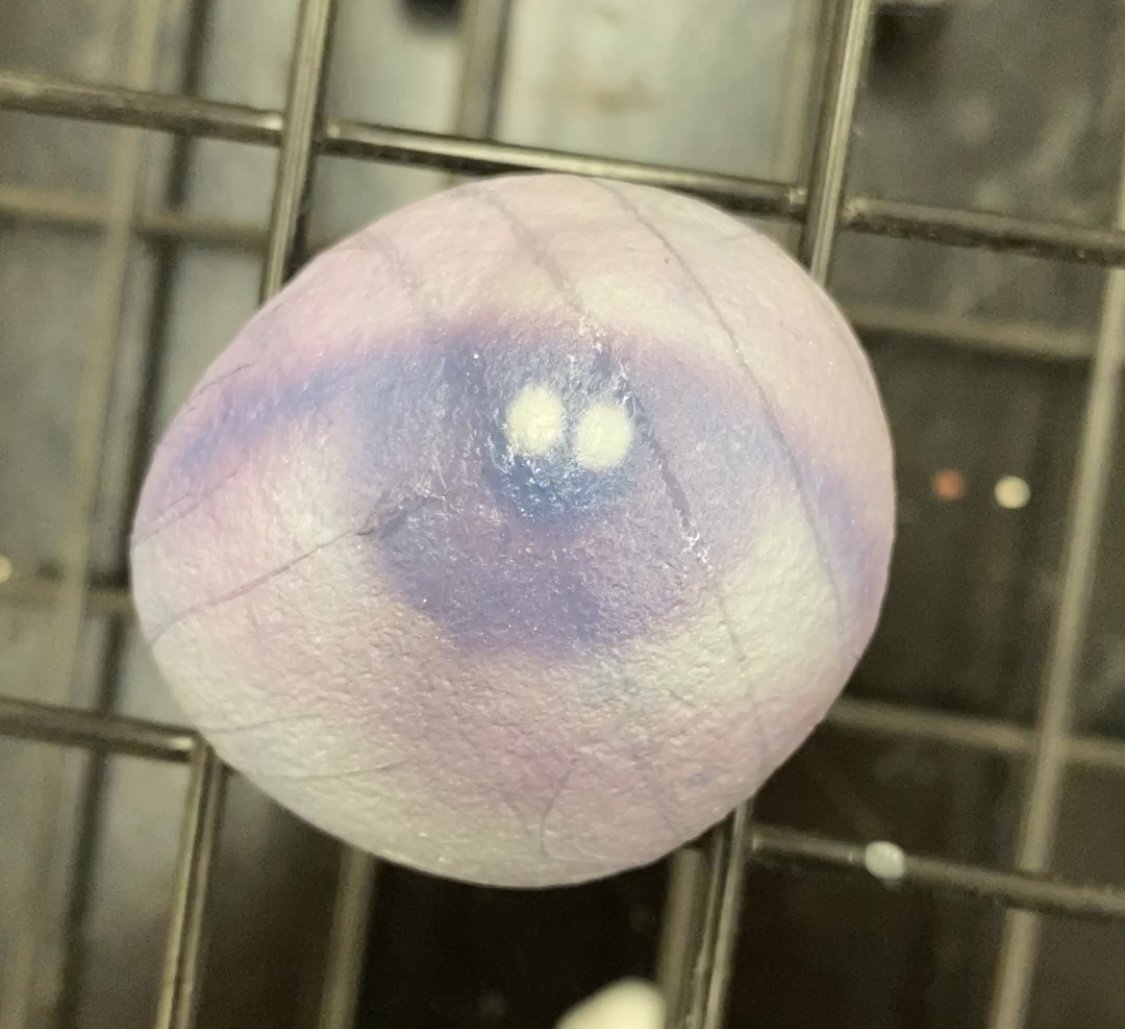

The package contained a very small, potent painting of George’s own right eye, floating uncannily against a monochromatic background. No other facial features anchored it, save a barely-there eyebrow. All focus was on the composition’s core, where a dark iris gazed ardently from behind a soft, love-drunk lid.

The Prince of Wales and Fitzherbert weren’t the only ones exchanging eyes in 18th-century England. Eye miniatures, also known as lover’s eyes, cropped up across Britain around 1785 and were en vogue for shorter than half a century. As with the royal couple, most were commissioned as gifts expressing devotion between loved ones. Some, too, were painted in memory of the deceased. All were intimate and exceedingly precious: eyes painted on bits of ivory no bigger than a pinky nail, then set inside ruby-garlanded brooches, pearl-encrusted rings, or ornate golden charms meant to be tucked into pockets, or pinned close to the heart.